Just over 100 years ago on 11 November 1914 – the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed V, and caliph of all Muslims, who had earlier signed a treaty with Germany, declared a holy war against Great Britain and her allies, “the mortal enemies of Islam”.

The ruler of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed V, and caliph of all Muslims called for Jihad.

The Turkish sultan’s call was answered in Egypt and Mesopotamia, and in Broken Hill, Australia where two “Turks” launched a suicide mission (jihad) under their homemade Turkish flag.

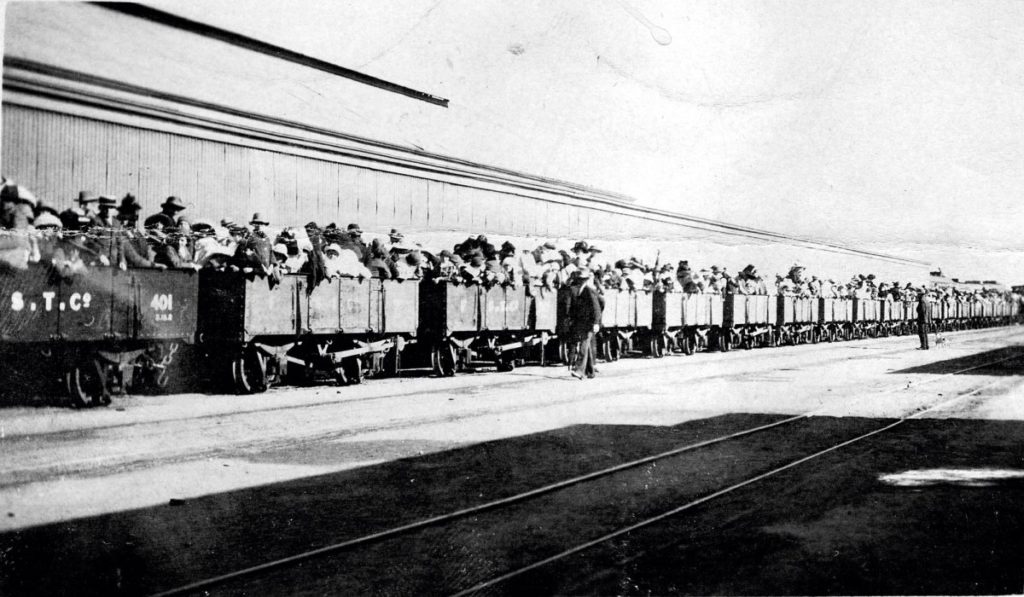

The target they had chosen for their Jihad suicide mission was a train of 40 open ore wagons carrying more than 1200 holiday-makers.

The picnickers initially thought that the shots were being discharged in honour of the train’s passing, but once their companions started falling, the reality sank in. Four people died as a result, police were called in. A 90 minute gun battle ensued during which armed members of the public arrived to join the police and military. An eyewitness later stated that Gool had stood with a white rag tied to his rifle but was cut down by gunfire. He was found with 16 wounds. The mob would not allow Abdullah’s body to be taken away in the ambulance. Later that day both bodies were disposed of in secret by the police.

James Craig, a 69-year-old occupant of a house behind the Cable Hotel, resisted his daughter’s warning about chopping wood during a gun battle and was hit by a stray bullet and killed. He was the fourth to die.

At “one o’clock a rush took place to the Turks’ stronghold”. An eyewitness later stated that Gool had stood with a white rag tied to his rifle but was cut down by gunfire. He was found with 16 wounds. The mob would not allow Abdullah’s body to be taken away in the ambulance. Later that day both bodies were disposed of in secret by the police.” —Wiki Leaks.

NEWSPAPER REPORT: “Dressed in their freshly laundered best summer clothes, some holding parasols, hundreds of lighthearted men, women and children chatted and waved as the train jolted forward and headed out towards the desert. Australia had been at war since August 1914 – many of these picnickers had brothers, fathers and sons in the Commonwealth Expeditionary Force that only weeks before had reached Suez. Yet this was a day to forget absent ones. On that Saturday morning, few places on earth were as peaceful as the red landscape surrounding Broken Hill, or so remote.

Top recommendations

- Casino Utan Spelpaus

- Casino Non Aams

- Crypto Casino

- Casino Non Aams Sicuri

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Migliori Casino Online Non Aams

- UK Casino Not On Gamstop

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Slots Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- Online Casinos

- Not On Gamstop Casinos

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- オンラインカジノランキング

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casino Online Non Aams

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Melhores Cassinos Online 2025

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Online Casino

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Best Non Gamstop Casino

- Crypto Casino

- Casino En Ligne

- Tous Les Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Tous Les Sites De Paris Sportifs Belgique

- Meilleur Site Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino Online Non Aams

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Casino En Ligne France

- Nouveau Casino En Ligne France

- Migliori Casino Senza Verifica

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne France

- Casino Fiable En Ligne

- Site De Casino En Ligne

- 토토사이트

- Migliori Casino Online Italia